8.1 Introduction

I am writing

this chapter in a style different to the rest of the thesis. A style that allows a descriptive yet analytical

flow enabling the reader to feel as though they are in the county of Cornwall

and offering a mental image and a sense of place. Raymond Williams uses such a style, with a

quality of writing techniques that I aspire to achieve.

The make

up of this chapter is a discussion on the overall findings of the three-year

research programme on the regional development of

Cornwall.

It recalls the roles of culture, industry, economics and society, and

their relationship with the historical background of

Cornwall, and their combined role in the

economic future of the county. I will

refer back to the theoretical concepts discussed in chapter 2 and their

relevance in disseminating the empirical part of the research. I consider this a key issue as the theoretical

concepts and the empirical data need to complement each other, in that the

theory brings some sense to the empirical work, and vice-versa.

8.2 Cornwall: A Sense of Place

“To enliven us

our mother said: 'When we leave

Plymouth

we shall come to a bridge, and once the bridge is crossed we shall be in

Cornwall'. We

jumped about, excited. All was anticipation, and it was unbearable to

wait. The train drew out of the station at last, and soon after there was

a strange rattling sound as the carriage wheels ran upon the bridge. ‘There.

Now we’re in

Cornwall’

said our mother, laughing. I stared out, disenchanted. For what was

different about this?” (du Maurier, 1967 pg4).

Imagine that you are

visiting

Cornwall

for the first time, here and now in the early part of the twenty first

century. Taking the most southerly route

via the A38[1]

trunk road, you have just driven over the Tamar road bridge that runs parallel

to the

Royal

Albert

Railway

Bridge built by Isambard

Kingdom Brunel in 1859 linking

London

to

Cornwall via

the newly established rail network. The

bridges link

South Cornwall to

England; I

wonder how many people crossing the bridges consider the importance of the rail

bridge to

Cornwall

in 1859? As du Maurier found, the

scenery only changes gradually but the culture and industry change almost

instantly. The introduction of the

railway in

Cornwall

led to industrial expansion in the county from the early 1860s.

The importance of the railway to

Cornwall

in terms of economy emerged through utilising the new rail network to transport

Victorian tourists from all over the

UK.

Prior to the construction of the Royal Albert Bridge in 1859, the only

bridge across the Tamar was one constructed in the fifteenth century at

Horsebridge (photo5), about twenty miles from the coast at Plymouth.

Photo 5: 16th Century

Bridge at Horsebridge on the Devon Cornwall border. Photo reproduced here with

the kind permission of Western Web Ltd 2003

The construction

of Brunel’s bridge and the subsequent rail link to

Penzance

opened up faster trade routes to South and

West Cornwall.

The railway link to

Cornwall

remains an integral part of the infrastructure that supports the Cornish

economy. True, there are demands for

greater funding for the rail network in

Cornwall,

funds that will undoubtedly improve efficiency and access to the western end of

the county. This is particularly

important considering the ongoing campaigns by environmental organisations to

encourage people off the roads and onto the railways.

One of the major problems with the rail network in

Cornwall is the speed of the trains. Due to the rail track following the coastline

in the south and over the hills and moors ‘…it [the railway] is not now

competitive with the car, particularly from here [Truro] to Exeter. It takes

one and a half hours by car and two and a half hours by train.’ (Rob Hitchen

Interview 2002). This causes problems

not so much for tourists but for commuters.

With the road infrastructure also in need of a major overhaul, due to

the increase in road traffic, add to this a poor rail service and the

eventuality is gridlock at peaks periods.

Personal experience driving into

Truro

in March 2002 took 45mins longer than necessary entirely due to heavy rush hour

traffic. For a region that is ‘seeking to regenerate’, there is a demand for

the rail and road infrastructure to improve, thus providing better access to

the employment opportunities afforded by the impetus of Objective 1 funding.

There is any number of claims to where regeneration should begin, ask any

representative of key stakeholders and each will offer a different option: the

physical infrastructure through rail, road and communications, the

concentration on job creation as the priority,

community capacity building, tourism development, and so on. They are all equally important and all

rightly treated as such, thus providing momentum in regeneration. What is crucial is that there is a visually

active overseer of regeneration. The overseer should manage through governance

the myriad stakeholders in the county.

Much as Foucault (1978) discusses in terms of governmentality in that a

strong ‘father figure’ – GOSW - to

control ‘the children’ – SWRDA, CCC,

community groups - is necessary to maintain a balanced and developing economy

and society.

8.3 Strange Buildings and Man -made Mountains

Continuing our journey through the Cornish countryside of narrow roads

bordered by ancient hedgerows, strange looking buildings begin to appear on the

horizon. They are relics of the tin

mining era, the pump houses that pumped water out of the deep tin mines. (Photo

6) These are probably the first

indications of a bygone mining culture in

Cornwall

and reflected on many postcards sent home by tourists to their family and

friends of their stay in

Cornwall. They remind me of the importance of the

mining industry in

Cornwall,

in the past, present and future tenses.

The Cornish born still relate to tin mining as an integral part of their

society. A society that has grown, similar

to Williams’ (1958) concept of a developing society, through ‘…active debate,

and amendment under the pressures of experience, contact and discovery, writing

themselves into the land.’ This is

particularly so, in the Cornish case, with the hundreds of pump house remains

found throughout

Cornwall. An old Cornish saying ‘Down every hole you’ll

find a Cornish miner’ embraces the reverence that the Cornish people hold for

the former tin mining industry.

Moreover, a poem by Patrick French (1997) summarises the Cornish

acceptance of the regeneration process from the decline of the mining industry

through the angst over the fishing industry and the culmination of a new

technological age reaching the county.

Photo 6: An Abandoned Tin Mine Pump House near St Just Cornwall

NEW OPPORTUNITIES

Cornwall

Was all

An engineer’s dream,

As they built and

exploited inventions with steam.

Its miners

Were finders

Of techniques all new,

Which they took round

the world -- and explained what to do.

And its seamen

Were toughened

By life out afloat,

Crewing steamers or

trawlers or local lifeboats.

Now mining’s

Declining.

‘Fact someone has

said:

One day he just woke

up and read it was dead.

But fishing

We’re hoping

Will not do the same,

Though’ daily some

strangers to our grounds lay claim.

I ‘spect we

D’reckly

Will hear on the news:

That the boats out of

Newlyn have got Spanish crews!

‘Tis no joke

For menfolk,

If their jobs they

lose,

And there aren’t any

options of new jobs to choose;

It’s computers

And software

Which these days

somehow

Are the country’s main

needs for new jobs right now.

The young lads

Of those dads

Find it easy. I s’pose

To them it’s as plain

as the tip of their nose.

There’s layout

And logout

And words like

splitscreen;

And passwords and

programs all part of the scene.

There’re formats

And inserts --

That’s just for a

start --

And a run and a

printout are also a part.

There’s data

To cater

For, modems and such

--

But to say it all now

is really too much!

At worst,

We must first

Establish and find

New skills to be

learned by the men who once mined.

They don’t shirk

Hard work

Of the manual kind,

But keyboards an’

suchlike they might find a bind.

But we must,

‘Cos its just

And its right and its

proper,

Teach them to know

what technologies offer.

Scattered

throughout the county are mining villages where communities are beginning to

respond to the processes of regeneration and are involving themselves in issues

surrounding capacity building. They are

encouraged by bodies such as the SWRDA, the County and District Councils and

community development officers to develop ideas for the economic regeneration

of their community. The District Council

is instrumental in encouraging the communities to evaluate, discuss and act

upon concepts for regeneration. They do

so through an ‘integrated and holistic approach’ that ‘…provides a wide ranging

programme of support and provision’ (North Kerrier IAP 2001: 17).

The development of the role of the various agencies involved with the

economic regeneration of communities follows the regulationist view of

restructuring a new mode of regulation.

It is reasonable to accept that Cornwall suffered a breakdown in modes

of regulation thus leading to its current ‘crisis’ in that the economic decline

in the region became a major concern.

Hence, the injection of funding via the Objective 1 scheme in 2000 was

in recognition of this. The new mode of

regulation in this instance is through the development of the integration of

all the stakeholders involved in economic regeneration. The endogenous system of development

encourages the more holistic nature of regeneration. It involves the community from the outset and

has potential to ensure the continuation of the development process in years to

come.

‘Regulation theory seeks to

integrate the analysis of political economy with that of civil society and the

state to show how they interact to 'normalize' the capital relation.’ (Jessop

1999: 64)

Thus, the

evidence collected through the interviews with key stakeholders and the

analysis of policy documents offers a theoretical perspective to the issues

revolving around social and economic regeneration.

The journey continues along the A38 to St Austell, now famous for the

location of the Eden Project built in one of the former china clay

quarries. The Eden Project is the

largest visitor attraction in

Cornwall. It attracts approximately 1.8million visitors

per year. 95% of its employees are sourced locally, of which 50% were

previously unemployed (Eden Project 2003).

Additionally, the creation of about 1,700 jobs distributed between

Cornwall and the counties

of

Devon and

Somerset indicate a considerable boost to the

economy in the region. It is ideally

located for the day-tripper from

Bristol

(approximately 2hrs by car) or the holidaymaker in St Ives (1hr by car). In March 2002, GOSW announced that the Eden

Project would receive further Objective 1 funding of £1.75million in addition

to the £1.5million from the SWRDA, to build the Eden Foundation building, which

will house facilities for academic researchers from around the world. Therefore, as the Eden Project expands so to

will the local economy through increased employment. Here, on a large scale is evidence that

co-operation between business, communities, the local authority and fund

managers from SWRDA and GOSW operate together to produce a successful outcome

to a major development project. However,

let us not get carried away with the success of the Eden Project. Close by, in St Austell and the surrounding

area there is still large areas suffering from high unemployment caused by the

reduction in clay mining.

Aside from the recently re-opened tin mine in Redruth, the china clay

mining area of St Austell is all that remains of the mining industry in

Cornwall. The china clay mining remains one of

Cornwall’s success

stories. After over 300 years, it

continues to support the local economy, although due to modern mining methods

the numbers of employees is now at a little over 2200 it peaked at over 5000 in

the 1970s. As you drive, you will notice

a number of cone shaped hills these are fabricated structures, similar to those

that adorn the landscape in coal mining districts of

South

Wales. They are made not of

coal slag as in

South Wales but of sand and

mica separated from the clay in the refining process. The mounds have, over many years, ‘grassed

over’ and some look more like natural landscape features similar to the smaller

burial mounds that adorn the Wiltshire countryside around Stonehenge.

St Austell town centre is predominantly of 1960s architecture and much of

it now owned by the SWRDA and scheduled for redevelopment during 2003. The redevelopment programme is part of a

scheme that involves Restormal District Council, who, along with the SWRDA

organised a number of consultations with the local people on how the rebuilding

should look. ‘An architect has just been

selected, there has been a lot of public consultation, but out of that will fly

Objective 1 projects.’ (Stephen Bohane

interview 2002) This is continuing the process of involving the communities

even in the larger scale projects. It is

reflective of the attitudes towards economic development required by central

government. Since the inauguration of

regeneration planning in

Cornwall

in the 1980s, stakeholders have struggled to encourage community involvement.

‘It’s quite

challenging to get people involved, not just here but in the whole of

Cornwall. When I was working at RCC (Rural Cornwall

Council) we reckoned that there is probably a network of 5000 people in

Cornwall who are involved

in the community voluntary sector. And

if you go to meetings you tend to see the same faces again and again, with

different hats on. In this area there is

a particular problem because of the social deprivation. The problems of

Cornwall are magnified several fold in that

if you don’t have fairly well paid jobs or jobs with any permanence you lose

your intellectual capital. And you also

lose people who are prepared in their spare time to sit on boards and

committees and that kind of thing. So

that makes it more challenging to get people through the doors’ (Stephen

Horsecroft interview 2002).

However, since

the late 1990s a shift in community involvement on regeneration projects is

evolving. This is partly due to the

steady influx of incomers in to the county seeking to ‘get involved’ with

village community life. The population

of

Cornwall is

now made up with a 50 – 50 split between those born in the county and incomers

(CCC 2003). Thus, the influence of

incomers is helping to re-kindle the spirit of the communities with the

assistance of the external influences of the SWRDA and County Council. Communities are now encouraged to involve

themselves in the decision-making process that revolves around regeneration. The inclusion of the community in

decision-making helps to establish a core element in the decision-making

process that will sustain the drive for a better community in both social and

economic terms. All of these points are

indicators of a system of governance and as such suggest that there is a

definite shift from government to governance in

Cornwall as described by Painter &

Goodwin (1996) as a mode of social regulation.

The use of regulation theory and political ecology methodology helped in

establishing the criteria that formulate a system of governance. Investigation into the roles of the various

stakeholders through interviews, led to an understanding of how local

government is developing a more fluid method of regeneration. By this, I mean that regeneration is not

something that is ever completed. It is

an ongoing process, continually put under pressure through changes in

government, both local, and perhaps more directly, central government. Thus, stakeholders must have a built in

strategy that enables the continuation of a system of governance that embraces

community involvement regardless of which political party is in government. There

is evidence that the shift from government to governance is a positive way

forward. The relationship between the

local communities and the policy makers is now one of working together rather

than one that is leaning towards exogenous tendencies. Where previously

communities and outside agencies talked but no one listened, the groups now

come together to negotiate and plan projects.

In order to maintain steady growth in the economy of

Cornwall, stakeholders must continue to

include communities in development processes and not revert to the top down

approach of previous governments. A mode

of social regulation is dependent on a solid network structure that integrates

all of those involved with regeneration in Cornwall. Without the network structure a repeat of

what Goodwin terms ‘crises’ in that a

crisis is a rupture in the reproduction of a social system may ensue. In this context, it would mean a ‘crisis in governance’ similar to the

crisis tendencies of the Keynesian welfare state, crisis in Fordism, and crisis

tendencies of the British state discussed in an earlier chapter.

The shift to a system of

governance in

Cornwall

follows Jessop’s belief that there is a ‘…resurgence of regional and local

governance’ (Jessop 1996 pg271) a system that includes new technology,

training, education, research and development, public infrastructure and

cultural industries (Jones & MacLeod 1999).

The integration of these products of governance into the networking of

stakeholders is what will result in a steady yet fruitful growth in the

economic regeneration and social welfare of

Cornwall.

During the 1990s, commentators such as

Florida 1995, Cooke and Morgan 1993, Amin

& Thrift 1994, and Storper 1995 discussed the animation of ‘learning’,

‘innovative capacity’, ‘institutional thickness’,

(Jones & MacLeod 1999) as elements of future economic competitiveness and

prosperity (Jessop 1997). Again, there

are indications that these elements are formulating to help provide inclusion

of all the beneficiaries in the socio-economic development process in

Cornwall. Some of the terminology has changed; ‘learning’ is now educational development, ‘innovative

capacity’ is capacity building, ‘institutional thickness’ represents the stakeholder networks.

Nonetheless, different terminology

does not detract from the fact that there are now positive strides towards the

creation of workable regimes in which communities, businesses, government offices,

regional agencies and local authorities all work together in their desire to

improve social welfare and the economy of any given region. The Objective 1

programme is an example of how developing and encouraging communities,

businesses, government offices, regional agencies and local authorities come

together to regenerate a regional economy.

8.4 Single Carriageway equals Congestion, Dual

Carriageway Equals Ecological Destruction - and Economic Growth

The journey continues, up to join the A30 trunk road, the main arterial

road in

Cornwall. It is here, along Goss Moor that construction

of the new dual carriageway will soon commence.

The demands for the new road have echoed throughout the region for

decades and will surely benefit local businesses and local communities. It is perhaps the one instance in this thesis

where political ecology research methods really come to the forefront. Political ecology, as an appropriate tool for

this research encompasses the ideologies that direct resource use, and

influence which social actors benefit and which are disadvantaged (Stonich

1998). The Goss Moor road project will

devastate a large area of moorland much of which is a designated Site of

Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). However, because of many years of

consultation, debate and environmental impact research, the benefits to the

communities in the area out way the concerns of environmentalists thus, the

construction of the road is to go ahead.

It epitomises the role political ecology theory and methodology can play

in analysing issues that affect not only the natural environment but also the

impacts on humankind. Political ecology

is not just about investigating the role of humankind on the environment it is

also about the inter-relationships of political bodies (decision makers), local

communities (receptors) and used to critically assess the cultural aspects to

economic and ecological sustainability.

This is also applicable to those

communities involved in developing networks that are striving to improve the

socio-economic status of the region. The

new road across Goss Moor will improve access to

West

Cornwall, and new businesses, already in-situ, will be in a

position to offer their customers speedier delivery of goods. One such company is Borders Books, who have

recently completed the move into a new factory at St Columb Major at the

Western end of Goss Moor, built with support from both the SWRDA and Objective

1 is ‘…the biggest factory to be built in Cornwall for years.’ (Stephen Bohane

interview 2002).

Access is a major issue in

Cornwall,

yet there are those who believe that access is not that important and offer a

variety of reasons as to why construction of the new road should not go ahead.

They question the plausibility of economic growth through improved transport

access.

‘It is increasingly recognised

that improved communications act as a drain of resources away from peripheral

areas by increasing the possibility to centralise production and distribution’

(FOE 2002).

This is possibly so, however, I argue that concerning

Cornwall, a fluid transport infrastructure

will permit better two-way access for both employment and tourism. In 1999, 83% of visitors to

Cornwall travelled by car and 4% by coach

(CCCi 2003). Thus, the construction of the new dual carriageway is vital for

the continued economic growth in the county.

To the west of the Goss Moor construction site are a

number of large regeneration projects funded by the SWRDA and Objective 1.

Tolvadden

Development

Park

among others and the regeneration of Camborne, Redruth and Pool will benefit

from improved road access and encourage people into the county as well as those

already working there to remain.

‘…these business

parks are built for business and to meet business needs. Whether that comes ultimately from outside

the county or from expanding Cornish companies, I don’t actually see that it

matters. Emphasis actually is on

expanding Cornish companies if they develop and release space further down the

chain for other people to come in or whatever.

I think the priority is very much on providing workspace both offices

and factories for expanding Cornish companies although we are also interested

in encouraging inward investment’

(Stephen Bohane interview 2002).

To the north of

the new road is Newquay, from where Ryan Air has recently started to run

flights to

London. These flights bring tourists and business

people to

Cornwall

and they need good access to the major towns and holiday resorts. The importance of the new road will prevail

when Ryan Air open routes from Newquay to other destinations in

Europe. ‘Ryan air will definitely open other routes; it

is an open secret that they are looking at

Dublin and

Frankfurt

for future routes. Now that becomes

really, really interesting’ (Stephen Bohane interview 2002). A point expanded by Rob Hitchens (interview

2002)

‘In tourism

what we are getting in Cornwall is sort of critical mass of high profile

projects like Eden, National Maritime Museum in Falmouth, Tate Gallery in St

Ives, I think we have got enough things for charter flights groups to spend a

week in Cornwall, be bussed around to the different locations and take their

charter flight back home to Paris or wherever they came from. And we have got an airport that can take these

big aircraft.’

However, Rob

Hitchens also pointed out that there is a distinct lack of good sized hotels of

the type you see on the

Costa del Sol. There is an abundance of Victorian style

small hotels and guest houses but he believes that the larger hotels would

attract more people because they would all have the same sized rooms for the

same price. It is something that package

tour operators require in order to sell the holiday destination to its

customers. Yet there is a problem with

building such hotels in that only a few months per year will see high occupancy

and at present visitors to

Cornwall

are predominantly from the

UK

4.1million in 1997 compared to 340,000 from overseas

(Objective One Partnership Ch2). Of the

total number of visitors to

Cornwall

in 1997, only 34% stayed in a hotel the remainder stayed in guesthouses,

caravans and friends homes (CCCj 2003).

The local

authority acknowledges tourism as one of the main economic factors to enable

success of economic growth and stability in

Cornwall.

Nevertheless, to rely too heavily on tourism is to be over dependant on

fluctuating market forces. Hence the

need for the agencies of governance such as the GOSW, SWRDA and Cornwall

Enterprise to work in unison with the local authority to market

Cornwall as a place to

come and relocate a business. They also need to encourage the young to stay in

the county and study at the new university under construction in

Falmouth. With an ageing population in Cornwall, due in

part to the exodus of young workers to other parts of the UK, the new

university will not only help in keeping Cornish youth in the county it will

also attract young people from other parts of the UK who in turn may decide to

stay on in the county to work.

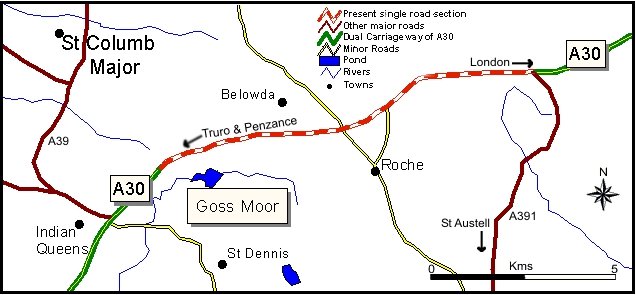

Map3:

Indicates the A30 over Goss Moor that is due for conversion into a dual

carriageway (created by the

author using ArcView GIS software)

8.5 Celtic Crosses, Gaelic Signs - ‘Made in

Cornwall’

As you drive further through the county, you become visually aware of the

increasing number of cultural indicators depicting Cornish history: Celtic

crosses, Gaelic script on road signs and the growing frequency of abandoned tin

mine pump houses. The growth and

development of the Cornish cultural identity is an integral part of the

development plans of Cornwall County Council.

Businesses are encouraged to integrate Cornish culture as an advertising

aid. Indeed, developing and using cultural

and regional identity is a major issue within the SWRDA (Stephen Horscroft

interview 2003). However, the policy

targets the whole of the South West region and not individual counties.

Cornwall

already has a very strong cultural identity and the County Council strongly

supports a ‘Made in

Cornwall’

scheme. The scheme was set up in 1991 to

help promote products made in

Cornwall.

‘

Cornwall is renowned for

its wealth of artistic talent and craftsmanship, and the description ‘Cornish’

is generally associated with quality. Unfortunately, like so many good things,

someone always tries to copy or impersonate the Cornish identity, and

descriptions such as ‘Cornish Ice Cream’, ‘Cornish Pasty’ and ‘Cornish Cream

Fudge’, which are in use daily by companies throughout the Country, are

examples of this.

The ‘Made in

Cornwall’ Scheme was developed

in 1991 in an attempt to identify the genuine Cornish produce. Under the

control of Cornwall County Council’s Trading Standards Service a logo was

introduced for local producers to use in association with their genuine Cornish

products.’ (CCC 2003)

Photo

6 ‘Made in

Cornwall’

Furthermore, Stephen Horscroft commented that:

‘…regional

bodies think that in order to attract inward investment we need to develop

identity. Actually, they have got it

wrong. Identities can be identified and

developed, but where you have got a strong identity or a strong regional brand

like you have in

Cornwall. You

have got something to work with already.

On Radio Cornwall there was a totally mixed up report because they said

the NFU were keen to encourage local people to buy local produce. Then the NFU

guy came on and started talking about West Country meat, so does that mean they

are trying to encourage people in

Cornwall

to buy Cornish produce which has a strong Cornish brand or buy beef from

Somerset? The first law of marketing is that you can’t

have two brands running at the same time. It’s a pretty fundamental issue that

is not dealt with.

These are issues

revolving around production and cultural identity an additional element is that

of the almost extinct yet recently revived Cornish language.

The Cornish language, now taught in many schools in the county, arguably

has little to offer in terms of economic contribution. It may help in maintaining the ‘Cornishness’

of

Cornwall and

it helps in retaining the unique culture that the county enjoys. The SWRDA now show recognition of the Cornish

identity as being separate from that of

England.

‘We had a lot of trouble when we

first came down with our signs being defaced.

Because at the time our signs, to some in

Cornwall, had rather a provocative strap line

saying

England’s

Leading Edge and that caused a few problems. Anything with the word

England in and

the English Rose on Tourist signs were subject to defacing. I directed our then marketing director to

change that and all our signs do not have that just have a web address but also

have, admittedly in fairly faint letters the words Working for Cornwall at the

bottom’ (Stephen Bohane interview 2002).

This is an

example of the benefits of the SWRDA having an office in

Cornwall.

It allows for the development of relationships between the ‘insiders’

and ‘outsiders’ permitting a more harmonious regeneration process. GOSW now

have an office in

Truro

and it is proving beneficial to the various officers working on behalf of the

local authority and the communities.

Stephen Horscroft commented:

‘…sometimes, like the neighbourhood nursery

project, you are going to need the applicant, myself and Government Office to

sit down around a table together to make sense of it and it is a good thing to

have them represented in the county’ (Interview 2002).

It appears that

following the introduction of offices in

Cornwall

by the SWRDA and GOSW, the interaction between central government

representatives, stakeholders and community leaders is reinforcing the role of

governance. It also vindicates central

government’s decision to encourage the endogenous development programme in the

regions.

The role of central government in some aspects has changed to a role of

governance, encouraging local authorities to develop their own system of

governance. They visualise the

introduction of the seven Regional Development Agencies (RDA) as a step towards

regional governance.

There are still tendencies to dictate to the local authority; the example from

the new Rural White Paper in November 2000 mentioned above is a case in

point. They actively encourage the

facilitation of training, networking and partnership development between the

local authority and the local business community. These few regulations combined with other

changes in regional policy have produced a system of local governance in

Cornwall that is a

combination of market forces and co-operation between regional agencies and

local communities.

8.6 West Cornwall – the Forgotten Region?

An indicator of the narrowing of the Cornish peninsula is the merging of

the two main arterial roads, the A30 and A38 to the west of

Truro.

They form the solitary major road down to

Penzance

and at Trencrom Hill near Lelant both the north and south coastlines of the

county are visible. The signs of the tin

mining industry become even more prolific with not only the pump houses but

also signposts to various renovated mines[7]

that are now tourist attractions. The

beaches of Hayle and St. Ives attract tens of thousands of visitors each year

and help contribute to much needed income necessary for the continued

development of the regeneration programme in the region.[8][41]

Having driven past the county town of

Truro with its magnificent cathedral, the

traveller arrives in

West Cornwall and the

District Councils of Kerrier and Penwith.

These two districts along with Restormal, perhaps more than any others

in

Cornwall are

the most in need of the benefits that social and economic regeneration can

provide. The employment figures in table

15 show the relatively high percentage of unemployed in the Kerrier and Penwith

with Penwith the highest at 4.7%. These

two regions are dependant on tourism to sustain economic stability let alone

economic growth. Hence, whilst these

figures depict the average for a twelve-month period they do not reflect the

seasonal trends in employment in the two districts as discussed in chapter

5.

|

Region |

% Unemployment Nov 2001 |

% Unemployment Nov 2002 |

|

Cornwall |

3.5 |

3.2 |

|

South West |

2.6 |

2.4 |

|

Great

Britain |

2.0 |

1.9 |

|

District |

|

|

|

Penwith |

5.4 |

4.7 |

|

Kerrier |

4.3 |

3.8 |

|

Carrick |

3.0 |

2.7 |

|

Restormel |

3.5 |

3.0 |

|

Caradon |

2.9 |

2.8 |

|

North Cornwall |

2.9 |

2.8 |

Table 15:

Unemployment figures for

Cornwall

and its Districts (source:

CCC i 2003)

Furthermore, due

to a skills mismatch in the new industries to

West

Cornwall, finding skilled labour is of concern to project

managers. Cemlyn, Fahmy and Gordon (2002) regard the skills mismatch as a major

issue revolving around social wellbeing. Stephen Horscroft (2002) supported

this:

‘There are

skill shortages in some areas like engineers, like play-workers, which are

quite crucial for the rest of the economy like the health service. But none the

less there’s underemployment and unemployment in core hard to reach areas and

we are sitting in one of those now [Redruth].’

To help

counteract the skills shortage the Construction Industry Training Board,

Jobcentre Plus,

Cornwall

College, the Learning and

Skills Council (LSC) Devon & Cornwall and the South West Regional

Development Agency, plus local, regional and national construction companies

set up a scheme called Construction Cornwall.

The scheme will help reduce the skills shortage in the construction

industry and associated fields. Emphasis

is on the retraining of the unemployed through to NVQ2 level and

apprenticeships where the Construction Cornwall scheme pay up to 45% of the

trainees wages. (Objective 1 media release 2002)

Within the Kerrier District Council area are the towns of Redruth and

Camborne. These two towns are the

flagship districts of an ongoing regeneration programme led by the SWRDA and

supported with Objective 1 funding. The

towns were perhaps one of the most deprived areas in

Cornwall, certainly in terms of employment.

The involvement of all the stakeholders, including community groups, reflects

the requirements of central government to shift local government to one of

governance. An example of how the

various stakeholders work together within the Kerrier district is the process

in which the team working on the Integrated Action Plan (IAP) for Kerrier have

a section each.

‘…the IAP

team here have got the area split into five, and each area has its own

regeneration group, which is an informal group to look at and advise on

projects, not just Objective 1 but other stuff.

So mine for Carn Brae Parish includes as an example, local councillors

at all three levels [parish, district and county], the local community

policeman, the local head teacher, local youth worker, that kind of thing.

(Stephen Horscroft Interview 2002)

The IAP team

reports to the IAP board with project ideas that emanate from meetings with the

community groups and local businessmen.

The IAP board assess the projects and submit a selection to Government

Office South West for further assessment and suitability for receipt of

Objective 1 funding.

Notwithstanding the drive for a system of local governance that

incorporates and encourages endogenous development, issues surrounding

continued development after Objective 1 funding ceases in 2006 require some

discussion. With the advent of some

Central European countries acceding to membership of the European Union in 2007

funding for regeneration from the EU is likely to flow towards the accession

countries. This is particularly so if

the SWRDA meets its regional target for average GDP above the EU threshold of

75%. Whist the regional average may well

stabilise above 75%GDP Cornwall’s GDP in 2002 was only 65%. The concerns are if

Cornwall fails to raise its GDP to the 75%

threshold will it still qualify for further Objective 1 funding. Stephen Horscroft (2002) considers it will:

‘Another thing

is if our GDP does decline we are almost certain to get another slice, we won’t

be competing with new Eastern European Countries and regions we’ll be in there

comparable with them. But even if O1 did

hit the spot and improve GDP you would need a few years of sort of exit money

to pick up residue and things like that.’

Robert Hichens (2002) considers that whilst the potential is there for

Cornwall to raise its GDP

to above 75%, in reality it is unlikely.

‘Objective 1

will undoubtedly do

Cornwall

some good but whether it will be possible to jack ourselves up to 80% or

something like that, I am not so sure. It seems to me highly unlikely, the

problem is everywhere else is moving forward too.’

It would appear that the regeneration process is actively encouraging

communication and co-operation between the various stakeholders. In addition, an element of acceptance that

the major players in the process, SWRDA and GOSW, are keen to help provide a

better and workable future now exists in the county. Even those who live in the die-hard regions

of

West Cornwall, Redruth, Camborne, St. Ives

and

Penzance now recognise that without the

input from outsiders and the requirement for locals to work with them towards

an improved social and economic life style; life in the county will remain a

struggle. Whether it is the role of

governance or not is not clear.

Nevertheless, this thesis clarifies that the role of communication

between all stakeholders involved in the processes of regeneration is

crucial. It has taken almost ten years

to convince the people of

Cornwall

that they must have belief in the assistance offered through the various EU

funded projects. Now that some of the

larger scale projects are complete, Borders Books, Eden Project,

Tolvadden

Business

Park,

and others such as the

Combined

University at Penryn near

to completion, confidence is growing.

There is a sense of good feeling developing in the towns and

villages. Summarised by a seventy five

year old lady from

Penzance who I met on a

recent visit (2003):

‘I have seen

many changes over the years, what with the closure of all the local tin mines,

and fishing becoming harder and harder. We, here in

Penzance

and

West Cornwall have struggled perhaps more

than most others in the county because we are so far from anywhere. We had all heard stories before about how

this organisation or that would come in and help us but they were false hopes. But now it is different, well at least it

appears to be. With all of this EU money

coming in, new roads being built to help link us better to the rest of

England things

are looking up. All we need is a faster

rail service to

London

and we should be made – but that’s too much to expect. The kids today living down here should have a

better life than many of us have had, and so they should. We have the best beaches in the country the

best weather and the best countryside so we should have the best way of life

but until now we haven’t.’

8.7 Journey’s End

So, the journey through

Cornwall

comes to an end. The drive from Redruth

down through to

Penzance reveals more relics

of the tin mining era, Celtic crosses decorate roundabouts and village

squares. Leaving

Penzance

passing the fishing

port

of

Newlyn, signs of

regeneration are visible in the construction of new fish processing

premises. Looking down on the fishing

port it is easy to see why so many artists, past and present saw Newlyn as such

a picturesque place. The tall masts and

booms of the fishing vessels, the nets hanging from the side, the fisherman

squatting on the dockside repairing nets as they have done for hundreds of

years. Hopefully, the regeneration

programmes will help in maintaining this coastal idyll.

The final stage of the journey takes us to Lands End just before sunset

when the sky is full of colour with wispy clouds diffracting the sunlight into

beams across the sky into the horizon.

However, instead of looking at the sunset look back at where you have

just come from and think. Think about

the people of

Cornwall,

how they have developed a great sense of pride in their county. One that sees some men send their pregnant

wife home from overseas, so that she can give birth to their child in

Cornwall hence he/she

will be truly Cornish. Think of what

Cornwall has had to offer

in the past and what it can for the future.

The new generation of children able to attend university in their own

county in the knowledge that once they graduate they will no longer have to

leave the county to find employment.

Think as to the reasons for all of this happening in just a ten-year

period. A development process that was

slow to start and to attain acceptance yet now appears to be flourishing, all

because people throughout all walks of life became involved and worked together

to produce what they hope will continue with future generations.

Thickness in this sense relates to a presence and

combination of institutions that are capable to support each other and

facilitate a base for economic development - networking. Nielsen (2002)

describes institutional thickness as:

|